Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press

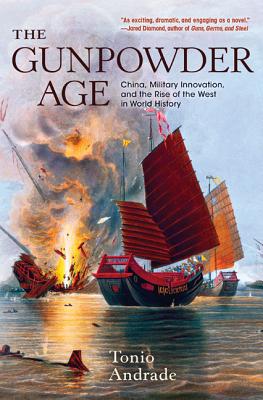

The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History

Key Metrics

- Tonio Andrade

- Princeton University Press

- Paperback

- 9780691178141

- 9.2 X 6.1 X 1.3 inches

- 1.6 pounds

- History > Military - Weapons

- English

Secure Transaction

Secure TransactionBook Description

A first look at gunpowder's revolutionary impact on China's role in global history

The Chinese invented gunpowder and began exploring its military uses as early as the 900s, four centuries before the technology passed to the West. But by the early 1800s, China had fallen so far behind the West in gunpowder warfare that it was easily defeated by Britain in the Opium War of 1839-42. What happened? In The Gunpowder Age, Tonio Andrade offers a compelling new answer, opening a fresh perspective on a key question of world history: why did the countries of western Europe surge to global importance starting in the 1500s while China slipped behind?

Historians have long argued that gunpowder weapons helped Europeans establish global hegemony. Yet the inhabitants of what is today China not only invented guns and bombs but also, as Andrade shows, continued to innovate in gunpowder technology through the early 1700s--much longer than previously thought. Why, then, did China become so vulnerable? Andrade argues that one significant reason is that it was out of practice fighting wars, having enjoyed nearly a century of relative peace, since 1760. Indeed, he demonstrates that China--like Europe--was a powerful military innovator, particularly during times of great warfare, such as the violent century starting after the Opium War, when the Chinese once again quickly modernized their forces. Today, China is simply returning to its old position as one of the world's great military powers.

By showing that China's military dynamism was deeper, longer lasting, and more quickly recovered than previously understood, The Gunpowder Age challenges long-standing explanations of the so-called Great Divergence between the West and Asia.

Author Bio

I’m part of a new field in historical studies known as Global History, which focuses on commonalities and connections between the myriad societies on the planet rather than on traditionally-defined political or cultural units. My core geographical area of expertise is China, but my research focuses on interconnections in the Early Modern Period (1500-1800) and on comparative history.

The main question that fascinates me is: Why did western Europeans, who sat on the far edge of Eurasia and were backward by Asian standards, rise to global prominence starting in the 1500s, establishing durable maritime empires that spanned the seas?

My first book, How Taiwan Became Chinese (2007), examined how Dutch, Spanish, and Chinese colonization met and competed in the Far East and asked why it was that the Chinese prevailed over the Europeans rather than the other way around, suggesting that political will – that is to say state support for expansion – was a key variable. My second book, Lost Colony (2011), examined the Sino-Dutch War of 1661-1668, Europe’s first war with China and the only significant Sino-European conflict until the Opium War of 1839–42.

It asked whether Europeans had – at this early date – any significant advantages in military and naval technology over China and concluded that they did, although not perhaps in the areas people might have expected. My third book, The Gunpowder Age (2016), looked more deeply into China’s military past, comparing it to that of Europe, and showing that China’s China’s dynamism was deeper, longer lasting, and more quickly recovered than has long been believed.

Books

- The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History (Princeton, 2016)

- Lost Colony: The Untold Story of Europe’s First War with China (Princeton, 2011)

- How Taiwan Became Chinese (Columbia University Press, 2007)

Articles in Journal of World History, Late Imperial China, Canadian Journal of Sociology, Itinerario, and Journal of Asian Studies, among others. Honors include The John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship and the Gutenberg-e Prize.

I accept Ph.D. students not just in Chinese history but also in the history of early modern European colonialism.

Syllabus for History 260: East Asia, 1500 to the Present

Emory Endeavors in World History (undergraduate history journal)

Education

BA, Reed College, 1992.

MA, University of Illinois, Urbana- Champaign, 1994.

MA, Yale University, 1997.

MPhil, Yale University, 1998.

PhD, Yale University, 2000.

Interests

Chinese history

Source: Emory College of Arts & Sciences

Videos

No Videos

Community reviews

Write a ReviewNo Community reviews