Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press

The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild

Key Metrics

- Thomas D Seeley

- Princeton University Press

- Hardcover

- 9780691166766

- 9.4 X 6.3 X 1.3 inches

- 2.3 pounds

- Nature > Animals - Insects & Spiders

- English

Secure Transaction

Secure TransactionBook Description

How the lives of wild honey bees offer vital lessons for saving the world's managed bee colonies

Humans have kept honey bees in hives for millennia, yet only in recent decades have biologists begun to investigate how these industrious insects live in the wild. The Lives of Bees is Thomas Seeley's captivating story of what scientists are learning about the behavior, social life, and survival strategies of honey bees living outside the beekeeper's hive--and how wild honey bees may hold the key to reversing the alarming die-off of the planet's managed honey bee populations.

Seeley, a world authority on honey bees, sheds light on why wild honey bees are still thriving while those living in managed colonies are in crisis. Drawing on the latest science as well as insights from his own pioneering fieldwork, he describes in extraordinary detail how honey bees live in nature and shows how this differs significantly from their lives under the management of beekeepers. Seeley presents an entirely new approach to beekeeping--Darwinian Beekeeping--which enables honey bees to use the toolkit of survival skills their species has acquired over the past thirty million years, and to evolve solutions to the new challenges they face today. He shows beekeepers how to use the principles of natural selection to guide their practices, and he offers a new vision of how beekeeping can better align with the natural habits of honey bees.

Engagingly written and deeply personal, The Lives of Bees reveals how we can become better custodians of honey bees and make use of their resources in ways that enrich their lives as well as our own.

Author Bio

My scientific work has primarily focused on understanding the phenomenon of swarm intelligence (SI): the solving of cognitive problems by a group of individuals who pool their knowledge and process it through social interactions. It has long been recognized that a group of animals, relative to a solitary individual, can do such things as capture large prey more easily and counter predators more effectively.

More recently it has been realized that a group of animals, with the right organization, can also solve cognitive problems with an ability that far exceeds the cognitive ability of any single animal. Thus SI is a means whereby a group can overcome some of the cognitive limitations of its members. SI is a rapidly developing topic that has been investigated mainly in social insects (ants, termites, social wasps, and social bees) but has relevance to other animals, including humans. Wherever there is collective decision-making—for example, in democratic elections, committee meetings, and prediction markets—there is a potential for SI.

To better understand how a group is optimally structured to possess swarm intelligence, we can examine natural systems that have evolved sophisticated mechanisms for achieving SI. For the past 30 years, I have done so by investigating the mechanisms of SI in honey bee colonies. A colony of honey bees is a model system for studying SI because it solves collectively a variety cognitive problems with impressive skill and because its mechanisms of SI are accessible to detailed observation and experimental analysis. Specifically, one can describe the problem-solving abilities of the whole system (colony), characterize the behavioral properties of the system’s components (bees), trace the routes of information flow between the components (signaling and cuing pathways), and manipulate the components’ behavioral properties and communication processes to test their roles in building swarm intelligence.

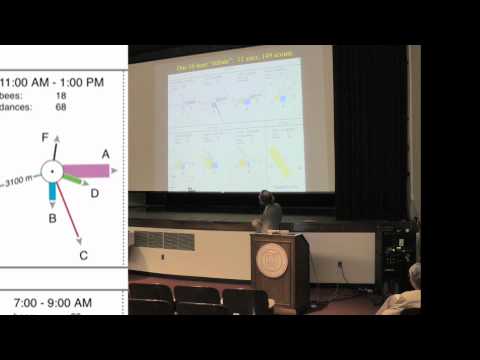

From 1980 to 1995, I directed most of my efforts at understanding how a honey bee colony solves the problem of allocating its foragers across an ever-changing landscape of flower patches so that it gathers its food efficiently, in sufficient quantity, and with the correct nutritional mix. This work is reviewed in detail in my book The Wisdom of the Hive (1995, Harvard University Press). Since 1995, I have concentrated on figuring out how a swarm of honey bees chooses a new home. This problem arises when a colony reproduces and the old queen bee and some ten thousand worker bees leave the parental hive to produce a daughter colony.

The emigrating bees settle on a tree branch in a beard-like cluster and then hang out there together for several days. During this time, these homeless insects do something truly amazing: they hold a democratic debate to choose their new living quarters. Exactly how they do so is reviewed in my book Honeybee Democracy (2010, Princeton University Press).

Remarkably, there are intriguing similarities between how the bees in a swarm and the neurons in a brain are organized so that even though each unit (bee or neuron) has limited information and limited intelligence, the group as a whole makes first-rate collective decisions.

For examples, in both systems the process of making a choice consists basically of a competition between the options to accumulate support (bee visits or neuron firings). And in both systems the winner of the competition is determined by which option first accumulates a critical level, or quorum, of support. Consistencies like these indicate that there are general principles of organization for building groups with SI, that is, groups that are far smarter than the smartest individuals in them.

The analyses of collective decision-making by honey bee colonies indicate that a group will possess a high level of SI if among the group’s members there is:

- 1) diversity of knowledge about the available options,

- 2) open and honest sharing of information about the options,

- 3) independence in the members’ evaluations of the options,

- 4) unbiased aggregation of the members’ opinions on the options, and

- 5) leadership that fosters but does not dominate the discussion.

At present, my main research interest is in the area of conservation biology: determining how honey bee colonies living in the wild are able to survive without being treated with pesticides for controlling a deadly ectoparasitic mite, Varroa destructor. Understanding how feral honey bee accomplish this will help beekeepers develop sustainable, pesticide-free approaches to beekeeping.

Preliminary work has shown that there remains a feral population of European honey bees living in the Arnot Forest, Cornell University’s 4200-acre research forest located 15 miles from Ithaca, NY. My work has also revealed that these bees have survived infestations of Varroa mites since at least 2002, that the mite populations in these colonies do not surge to high levels, and that this population of bees is not maintained by immigration of bees from managed (pesticide-treated) colonies living outside the forest.

I am currently investigating three possible mechanisms that can explain how the honey bees of the Arnot Forest are able to survive on their own: 1) these bees have evolved means of resistance to the mites, 2) the mites on these bees have evolved low intrinsic rate of reproduction (avirulence), and 3) these bees possess colony-level traits (such as small colony size and frequent swarming) that reduce mite populations.

Source: Cornell University

Videos

Community reviews

Write a ReviewNo Community reviews