Stanford Social Sciences

Stanford Social Sciences

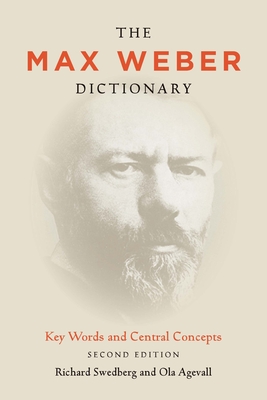

The Max Weber Dictionary: Key Words and Central Concepts

Key Metrics

- Richard Swedberg

- Stanford Social Sciences

- Hardcover

- 9780804783415

- 9.1 X 6 X 0.9 inches

- 1.7 pounds

- Social Science > Reference

- English

Secure Transaction

Secure TransactionBook Description

Max Weber is one of the world's most important social scientists, but he is also one of the most notoriously difficult to understand. This revised, updated, and expanded edition of The Max Weber Dictionary reflects up-to-the-moment threads of inquiry and introduces the most recent translations and references. Additionally, the authors include new entries designed to help researchers use Weber's ideas in their own work; they illuminate how Weber himself thought theorizing should occur and how he went about constructing a theory.

More than an elementary dictionary, however, this work makes a contribution to the general culture and legacy of Weber's work. In addition to entries on broad topics like religion, law, and the West, the completed German definitive edition of Weber's work (Max Weber Gesamtausgabe) necessitated a wealth of new entries and added information on topics like pragmatism and race and racism. Every entry in the dictionary delves into Weber scholarship and acts as a point of departure for discussion and research. As such, this book will be an invaluable resource to general readers, students, and scholars alike.

Author Bio

My two main areas of research are economic sociology and social theory. Economic sociology has been a vital interest of mine since the early 1980s; and today I mainly work on current topics. From early on I have also been fascinated by social theory, especially theorizing — what theorizing is and how it can be taught to students through practical exercises. My main work on this topic is The Art of Social Theory (2014). I have also worked on social mechanisms (see Social Mechanisms [1998]; ed. with Peter Hedström).

In the early 1980s I became interested in economic sociology, and I have had the pleasure to help this field grow into one of the major subfields in sociology. My contribution to this has consisted of general works as well as specific studies. For the former, see especially (ed. with Neil Smelser) Handbook of Economic Sociology (1994, 2005) and (ed. with Mark Granovetter) The Sociology of Economic Life (1992, 2001, 2011). For the latter, see e.g. (ed. with Victor Nee) The Economic Sociology of Capitalism (2005), (ed. with Trevor Pinch) Living in a Material World (2008) and (ed. with Hirokazu Miyazaki) The Economy of Hope (2017).

Along the road I have also made a number of studies of the major theoreticians in economic sociology, such as Joseph Schumpeter, Max Weber and Alexis de Tocqueville. The study of Schumpeter is formally a biography, but in reality centered around the relationship of economic theory to economic sociology. The study of Weber attempts to lay a theoretical foundation for economic sociology by following Weber’s leads in Ch.2 of Economy and Society. In my work on Tocqueville my interest in economic sociology comes together with that of theorizing. I emphasize the sociological aspects of Tocqueville’s analysis of the economy, but also how he experimented with different types of data and theories, to make sense of things. See Schumpeter – A Biography (1991), Max Weber and the Idea of Economic Sociology (1994) and Tocqueville's Political Economy (2009).

Besides social theory and economic sociology, I have also written on various other topics — such as the role of civic courage; (with Wendelin Reich) on George Simmel’s metaphors; on Rodin’s statue “The Burghers of Calais”; and (with Trevor Pinch) on Wittgenstein’s visit to Ithaca in 1949. These articles can be found on my webpage.

Today I mainly try to write sociological essays, with an emphasis on new ideas. The topics vary, from traditional ones in social theory to more unorthodox ones, with the same for economic topics.

Education

MM.L. (“Juris kandidat”), Faculty of Law, Stockholm University June 1970;

Ph D, Department of Sociology, Boston College May 1978.

Source: Cornell University

Videos

Community reviews

Write a ReviewNo Community reviews