Oxford University Press, USA

Oxford University Press, USA

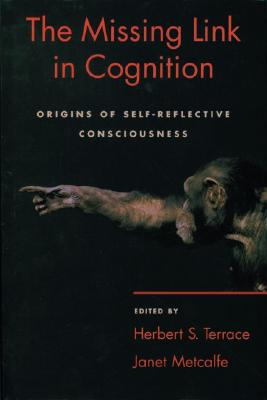

The Missing Link in Cognition: Origins of Self-Reflective Consciousness

Key Metrics

- Herbert S Terrace

- Oxford University Press, USA

- Hardcover

- 9780195161564

- 9.42 X 6.36 X 0.92 inches

- 1.55 pounds

- Psychology > Cognitive Psychology & Cognition

- English

Secure Transaction

Secure TransactionBook Description

Their debate focuses primarily on the underpinnings of consciousness. Some of the participants believe that consciousness depends on representational thought and on the mental manipulation of such representations. Is representational thought enough to ensure consciousness, or does one need more? If one needs more, exactly what is needed? Is reflection upon the representations, that is, metacognition, the link? Does a realization of the contingencies, that is, knowing that, in Gilbert Ryle's terminology, ensure that a person or an animal is conscious? Is true episodic memory needed for consciousness, and if so, do any animals have it? Is it possible to have episodic memory or, indeed, any self-reflective processing, without language?

Other participants believe that consciousness is inextricably intertwined with a sense of self or self-awareness. From where does this sense of self or self-awareness arise? Some of the participants believe that it develops only through the use of language and the narrative form. If it does develop in this way, what about claims of a sense of self or self-awareness in non-human animals? Others believe that the autobiographical record implied by episodic memory is fundamental. To what extent must non-human animals have the linguistic, metacognitive, and/or representational abilities to develop a sense of self or self-awareness? These and other related concerns are crucial in this volume's lively debate over the nature of the missing cognitive link, and whether gorillas, chimps, or other species might be more like humans than many have supposed.

Author Bio

The general focus of my research is the evolution of intelligence with specific emphasis on cognitive processes that do not require language. In my primate cognition lab, I have trained rhesus monkeys to learn various serial tasks involving arbitrary and numerical stimuli. For example, I have shown how monkeys can become expert at learning rote lists similar to those we perform daily when dialing a phone number or entering a password. Instead of responding to Arabic numerals the monkeys respond to photographs displayed on a touch sensitive video monitor.

I also study how monkeys learn ascending and descending numerical sequences (e.g., 1-2-3-4, 4-5-6 or 6-5-4) and how they generalize their knowledge of specific numerosities to novel numerosities. In these experiments, stimuli are constructed from geometric elements and differ in the number of elements they contain.

In other experiments I study social learning in situations where a student monkey learns a new list by observing an expert perform that list. More recently, I have applied a similar paradigm to study cognitive imitation in autistic children. Taken together, these experiments show that many complex skills can be performed without language and provide a basis for understanding what language adds to those skills.

Most recently I've written about the evolution of language, in particular, the evolution of the world. Separating the evolution of language into two problems, the origin of words and the origins of grammar makes an intractable problem more manageable. In infants, we have begun to understand how pre-verbal emotional and cognitive relations between an infant and her mother lead to the production of the infant's firs words. Among human ancestors, a case can be made that words were invented by Homo erectus. Both types of word learning are discussed in my recent book, Why Chimpanzees Can't Learn Language and Only Humans Can (2019).

Source: Columbia University

Videos

Community reviews

Write a ReviewNo Community reviews