Pinnacle Press

Pinnacle Press

Twenty-Two Years a Slave and Forty Years a Freeman: Embracing a Correspondence of Several Years, While President of Wilberforce Colony, London, Canada West

Key Metrics

- Austin Steward

- Pinnacle Press

- Paperback

- 9781374835399

- 9.21 X 6.14 X 0.55 inches

- 0.82 pounds

- History > General

- English

Secure Transaction

Secure TransactionBook Description

This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it.

This work is in the public domain in the United States of America, and possibly other nations. Within the United States, you may freely copy and distribute this work, as no entity (individual or corporate) has a copyright on the body of the work.

Scholars believe, and we concur, that this work is important enough to be preserved, reproduced, and made generally available to the public. To ensure a quality reading experience, this work has been proofread and republished using a format that seamlessly blends the original graphical elements with text in an easy-to-read typeface.

We appreciate your support of the preservation process, and thank you for being an important part of keeping this knowledge alive and relevant.

Author Bio

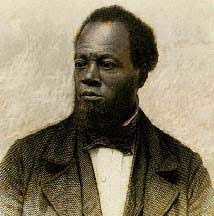

Austin Steward (1793-1865) was born in Prince William County, Virginia, to slave parents Robert and Susan Steward. When Steward was eight or nine years of age, his master, Captain William Helm, sold his Virginia plantation and moved his slaves to upper New York State.

Steward was hired out to various employers, but sometime around 1813, he escaped to Canandaigua, where he labored summers for a local farmer and attended a Farmington academy during the winter. In 1815 Helm located Steward, who retained his freedom with the assistance of the New York Manumission Society through a legal technicality in the state's Gradual Emancipation Law of 1799. About 1817 Steward moved to Rochester and, despite violent opposition by local whites, developed a successful grocery business during the 1820s.

He also taught a Sabbath school in the city. After being chosen by Rochester blacks to deliver an oration at their 5 July 1827 ceremonies celebrating slave emancipation in New York State, Steward became increasingly involved in the antislavery, temperance, and black convention movements. During the late 1820s, he served as Rochester subscription agent for Freedom's Journal and the Rights of All and hosted black reform meetings. He served as a vice-president at the first black national convention (1830).

In 1831 Steward joined the Wilberforce colony at the urging of a group of settlers. He organized and directed the settlement despite continual conflict with the Israel Lewis faction. Steward returned to Rochester in 1837, reentered business (this time with less success), and served on a committee appointed to oversee black schools in the city. After fire destroyed his business, he moved back to Canandaigua about 1842 and taught school. Despite these business failures, Steward regained his prominence among New York blacks during the early 1840s, presiding over New York State black conventions in 1840, 1841, and 1845 and simultaneously devoting new energy to the antislavery, black suffrage, and temperance causes.

His evangelical approach to these struggles culminated in his attendance at the 1843 Christian convention at Syracuse, which attempted to harmonize reform ideals with New Testament principles. In later years, Steward's age forced him to localize his efforts; he chaired local black meetings, served as Canandaigua's subscription agent for the National Anti-Slavery Standard, and was a vocal opponent of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. He wrote and published his autobiography, Twenty-Two Years a Slave, and Forty Years a Freeman, in 1857; it sold well, and three other editions were printed during the following decade.

The terminal illness of his talented daughter Barbara during 1860-61 placed Steward in a precarious financial situation and prompted his return to Rochester to sell copies of his narrative and to seek aid from former friends. Although he entertained the idea of going south to teach black contrabands during the Civil War, he remained in Rochester until his death.

Source: University of North Carolina Press

Videos

No Videos

Community reviews

Write a ReviewNo Community reviews