Kirk Savage

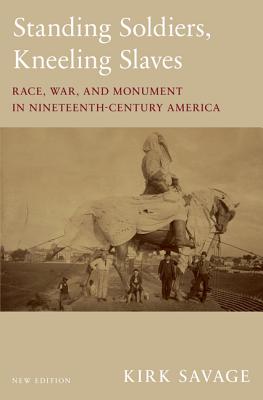

Kirk started writing about public monuments as a freelancer, and got into art history to feed his habit. Monuments combined many of his passions: sculpture, architecture, landscape, urban development, and politics. He decided to do his dissertation on Civil War monuments because they were almost everywhere but no one seemed to pay any attention to them, certainly not art historians. Not long into the project one of his advisors mentioned that he would need to deal with slavery and race. And so began a long learning curve that is still bending in front of him, hopefully toward justice.

In the years since, he has taught and written about public monuments and public art as they intersect with issues of loss, trauma, deindustrialization, militarism, and racial justice. As a scholar and teacher, he takes seriously the responsibility to reckon honestly with the past, bearing in mind Ta-Nehisi Coates’ admonition, “You must struggle to truly remember this past in all its nuance, error, and humanity.” Because monuments are a microcosm of the world their makers hope to enforce or to invent, every research project necessarily has social, political, and ethical dimensions.

With much of the world now finally turning its attention to the legacies of white supremacy built into the memorial landscape, Kirk has been working more intensively with artists, planners, preservationists, and activists in the public sphere who are looking for new ways forward. He is proud to be serving on the advisory board of the innovative organization Monument Lab, and to consult with other organizations that are reexamining their intersection with – or their stewardship of – the memorial landscape.

Concurrently, he has developed a strong interest in indigenous studies through the work of some extraordinary graduate students at Pitt, and through a collaboration with his wife Elizabeth Thomas on a new book project. His Father’s Son: Yonaguska, Will Thomas, and the Forgotten History of Cherokee Resistance on the Appalachian Frontier tells the story of the extraordinary Cherokee chief Yonaguska (1760-1838) and his agent and adopted son William Holland Thomas (1805-1893), and how one family descendant has come to terms with the repression and manipulation of this history.

Another ongoing project taps his lifelong interest in cemeteries. “The Art of the Name” uses the example of an early federal soldier lot created in a Pittsburgh cemetery to examine the complex and contradictory movement of bodies, names, and memorials after the Civil War.

Source: University of Pittsburgh

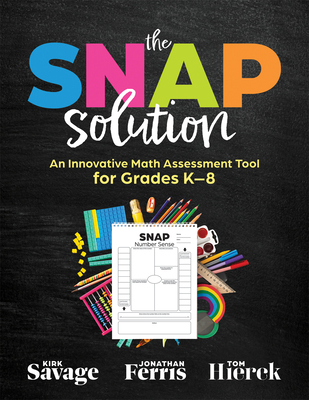

Books by Author

Videos